History & Exploration of the Libyan Desert

In ancient times, all large Egyptian oases, (with the possible exception of Farafra) were inhabited, and apparently supported a much larger population and cultivated area than today. The oases are filled with scattered remains of Ancient Egypt and Greco-Roman periods. However there is no evidence that outside the direct caravan routes to the oases, and areas close to the Nile valley, the ancients ventured anywhere in the deep desert.

In medieval times, until being closed by the Mahdi uprising in the Sudan, one of the major African trade routes crossed the eastern Libyan Desert, starting from the Darfur in the Sudan, and leapfrogging a series of small uninhabited oases in the south till reaching Kharga oasis, and terminating in Assiut in central Egypt. This road, the ‘Darb el Arbain’ (the forty days road) became infamous due to the main merchandise carried. Each year slave caravans started off with as much as 80 thousand unfortunates on the forty days march (not counting rest stops at oases), and usually no more than 20,000 reached Assiut, and the slave markets of the middle east. The mortality rate was similarly high among the beasts of burden, and to this day the route of the Darb el Arbain is marked with the white bones of camels, and the occasional human skeleton.

Except for the polar regions, the Libyan Desert remained one of the last large unexplored ‘blank spots’ by the early part of this century. Its exploration was limited by the endurance of camels, which can make a maximum of three hundred kilometres between wells, effectively limiting their range into the unknown to 150 km out of known water sources. In 1873 Gerhard Rohlfs, a German explorer, with backing from the Khedive of Egypt, ventured out from Dakhla to cross the Great Sand Sea to Kufra. However the dunes proved too formidable to his heavily laden camel caravan, and he was forced to turn north at a point he called "Regenfeld" on account of the rain shower experienced there. He continued in the valleys between the dunes till Siwa, and later reached Kufra from the North, as the first European (only to barely escape with his life due to the hostile reception). At the turn of the century the Englishman, Harding King made a series of camel journeys radiating from Dakhla and Farafra, but at the close of the first world war much of the interior of the Libyan desert was totally unknown, due to the lack of water, the impenetrable Sand Sea, and the hostility of the Kufra based Senussi to all outsiders.

Harding King (as has Wilkinson some eighty years earlier) has recorded legends of lost oases deep in the desert, including the famous ‘Zarzura’ oasis, a mythical place with hidden treasures. More realistically, natives have spoken to Wilkinson about three fertile valleys a couple of days march west of Dakhla, and of the hitherto unknown Kufra group of oases beyond. Legend also spoke of ‘black raiders’ occasionally attacking the Egyptian oases from the west, and then disappearing west again. Once supposedly a pursuit discovered a depot of water jars used by the raiders, which were destroyed. As in the meantime Kufra proved to be reality, there was reason to suspect that the legendary places do exist. This was further supported by the discovery in 1918, at about three days distance out of Dakhla, of a shattered stockpile of pottery jars, with Tobou markings, proving that the raiders in fact did come from Kufra.

|

The first major expedition to the interior was made by Ahmed Hassanein Bey, an Oxford educated Egyptian of bedouin descent, who could obtain the permission of the Senussi to pass through Kufra, in the autumn of 1923. Hearing local rumours of ‘lost oases’ to the south, he steered his caravan to that direction, and discovered the mountains of Arkenu and Uweinat (Ouenat), with their vegetated valleys and wells. Hassanein was the first to report of rock engravings at Karkur Talh, the northern valley of Uweinat, "apparently of great antiquity". From Uweinat, he continued south, explored the highlands of Ennedi, and terminated the traverse of the unknown at el Fasher, some 1500 km to the south of Kufra. |

|

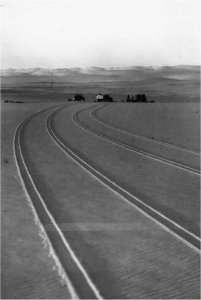

The discovery of a new water source at the very heart of the unexplored region, plus the advent of the motor car enabling far greater distances than previously possible by camel rapidly opened the interior. Prince Kemal el-Din was the first to reach Uweinat by motor car, and during the route from Dakhla, discovered the Eastern edge of the vast sandstone plateau occupying much of the land between Uweinat and the southern flanges of the Sand Sea. The prince named the plateau Gilf Kebir (great wall) on account of its impenetrable solid wall like appearance. On another trip, the prince has located the cairn built by Rohlfs at Regenfeld, recovering the document left there by the Germans, and replacing it with his own (starting a tradition prevailing to this day among travellers of the Western Desert). The prince also found some rock paintings alongside the engravings at Uweinat, and made the first scientific publication, raising the interest of the outside world.

|

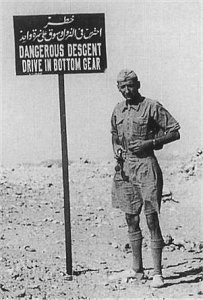

In the late twenties and early thirties most of the unknown was traversed and mapped by a handful of explorers. Ralph Bagnold, and Kennedy Shaw, Both British officers, László Almásy, a Hungarian gentleman-adventurer, and Patrick A. Clayton, of the Desert survey, all took their part. Bagnold and Almásy were the first ones to venture with ordinary motor cars into the deep desert, Bagnold successfully conquering the Sand Sea in 1930, while Almásy made the first motor car trip from Cairo to Khartoum in 1926, then traversed the hitherto unexplored section of the Darb el Arbain from Selima to Kharga in 1929. In the mean time, following the first ventures, Clayton and the Desert survey was extending systematic mapping of the western desert ever further westwards, while Douglas Newbold and Kennedy Shaw, in one of the last great camel journeys, surveyed much of the desert lying in the northern Sudan. |

|

In 1932 Almásy and Clayton, together with a young Englishman, Sir Robert Clayton East Clayton, organised a major expedition to survey the unknown western side of the Gilf Kebir, and for the first time the surveying kit included an aeroplane, a Gypsy Moth belonging to Robert Clayton. This expedition glimpsed three hidden valleys with vegetation from the air in the northern Gilf Kebir. While all efforts to reach them on land failed, the next year Almásy and Clayton on separate expeditions succeeded in entering them, Clayton the two to the east, Wadi Hamra and Wadi Abd el Melik, Almásy Wadi Talh to the west. These wadis were confirmed by natives of Kufra to be the ‘three wadis’ the Dakhlans have referred to Wilkinson, and possibly they were the inspiration for the ‘Zarzura’ legend. On the same 1933 expedition Almásy also reached Regenfeld (performing the obligatory exchange of messages), and a magnificent series of paintings were discovered at Ain Doua at Uweinat, above the well, in caves formed by the gigantic granite boulders lying on top of each other. The same autumn, on yet another expedition, Almásy discovered painted ‘caves’ (rather hollows) at the base of the cliff in the western Gilf Kebir, at Wadi Sora (the "Valley of Pictures"), containing among others the now famous figures of the "swimmers". |

|

The strategic importance of Uweinat with it's sole water-source for hundreds of kilometres did not go unnoticed by the acting colonial powers. Following the capture on Kufra in 1931, the Italians set up a small military post at Ain Doua, substantiating their claim on a wedge of land between southern Libya and French Central Africa, the "Sarra triangle" that was considered Sudanese territory. After a few years of ignorance, the British finally responded by setting up a similar garrison near Bir Murr, along the southern side of Uweinat. After much diplomatic huffing and puffing, the British have ceded the Sarra triangle to Italy, and military interest in he desert dwindled for awhile.

In 1935, W.B.K. Shaw led a motorcar expedition that traversed virtually all of the Libyan Desert between Siwa and El Fasher. During this trip the expedition discovered a series of broad transverse valleys, and a new painted rock shelter (Mogharet el Kantara, or Shaw's cave).

|

It is clear, that while all these explorers were truly addicted to the desert, and (apart from P.A. Clayton, who did it for a living) made their travels primarily for their own pleasure, their backers definitely had a vested interest. Their gained experiences were of great military value in the War. In 1940 Bagnold formed the Long Range Desert Group, with the objective of carrying out surveillance and raids deep inside (Italian) enemy territory in the desert. Both Shaw and Clayton were deeply involved, and the LRDG succeeded in a number of daring feats, including the raid on Murzuq in the Fezzan, and the capture of Kufra oasis together with the free French. For a period of two years Kufra was supplied by truck convoys starting from Wadi Halfa in Sudan, making their way via Jebel Kamil to Wadi Firaq in the Gilf Kebir, then along the western side of the Gilf to Kufra. Throughout the later part of the North African campaign, the LRDG remained active, first from a base in Kufra, then from Siwa as the action started centring on the northern coast. In the meantime Almásy, attached to Rommel’s staff, was entrusted with a daring project, to drop two German agents into Egypt. Almásy started from Jalo oasis, traversed the Gilf Kebir along the el ‘Aqaba pass, crossed Kharga, and dropped the agents in Assiut, then returned unnoticed the same way. |

After the war the western desert became quiet again. A few expeditions ventured out to Uweinat and the Gilf Kebir, the most notable being the Belgian expedition in 1968-69, which discovered a large number of unknown prehistoric paintings in the upper reaches of Karkur Talh at Uweinat. Later the joint prehistoric expedition, under the directorship of Fred Wendorf of the Southern Methodic University carried out a major prehistoric survey of the south eastern part of the desert over a number of seasons in the eighties, while the Heinrich Barth Institute of the University of Cologne carries out ongoing archaeological and geological work in the Gilf Kebir area, and the Wadi Howar in the Sudan.

|

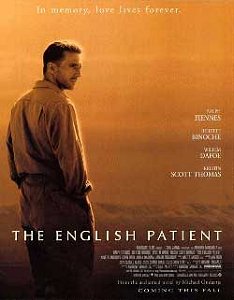

"The English Patient" |

||

|

In 1996 the movie "The English Patient" raised public interest, if not awareness, of the Libyan desert, and the person of Almásy. While the plot of the movie was pure fiction, based on a novel by Michael Ondaatje, certain characters and scenes were based on real people & places. The "cave of swimmers" does exist, at Wadi Sora in the western Gilf Kebir, and László Almásy was a living person, who did add considerably to our knowledge of the Libyan Desert. (Also the ‘Cliftons’ were loosely based on Sir Robert East Clayton and his wife, Lady Dorothy Clayton). |

| SEE ALSO: |

|

|